For Nikki Gigi Aytona Legaspi-Pelayo, a normal day means getting hands-on with medical techniques, immersed in patient simulators and procedural stations. In medical school, the spotlight often shines on theory, and for good reason. Students spend hours buried in concepts and memorising endless lists. But at the Clinical Performance Centre (CPC), it’s about making those theories real. It’s where students learn clinical skills in a setting designed to simulate actual practice.

Since joining Duke-NUS in 2022, long-time educator Legaspi-Pelayo has worked as an Education Associate II in Clinical Skills, part of the core teaching team for CARE procedural skills, which runs across Years One, Two and Four. Her bread-and-butter? Supporting students in their learning through self-directed but supervised practice—helping them build competence and confidence in essential clinical procedural skills.

“What we teach them are the procedural skills listed in the MOH guidelines required for them to be safe and competent doctors. These skills include the proper wearing of personal protective equipment (PPE) and even basic skills such as hand hygiene,” she explained.

As students progress, they move on to more complex techniques, mastering more advanced skills such as arterial blood gas collection and catheterisation.

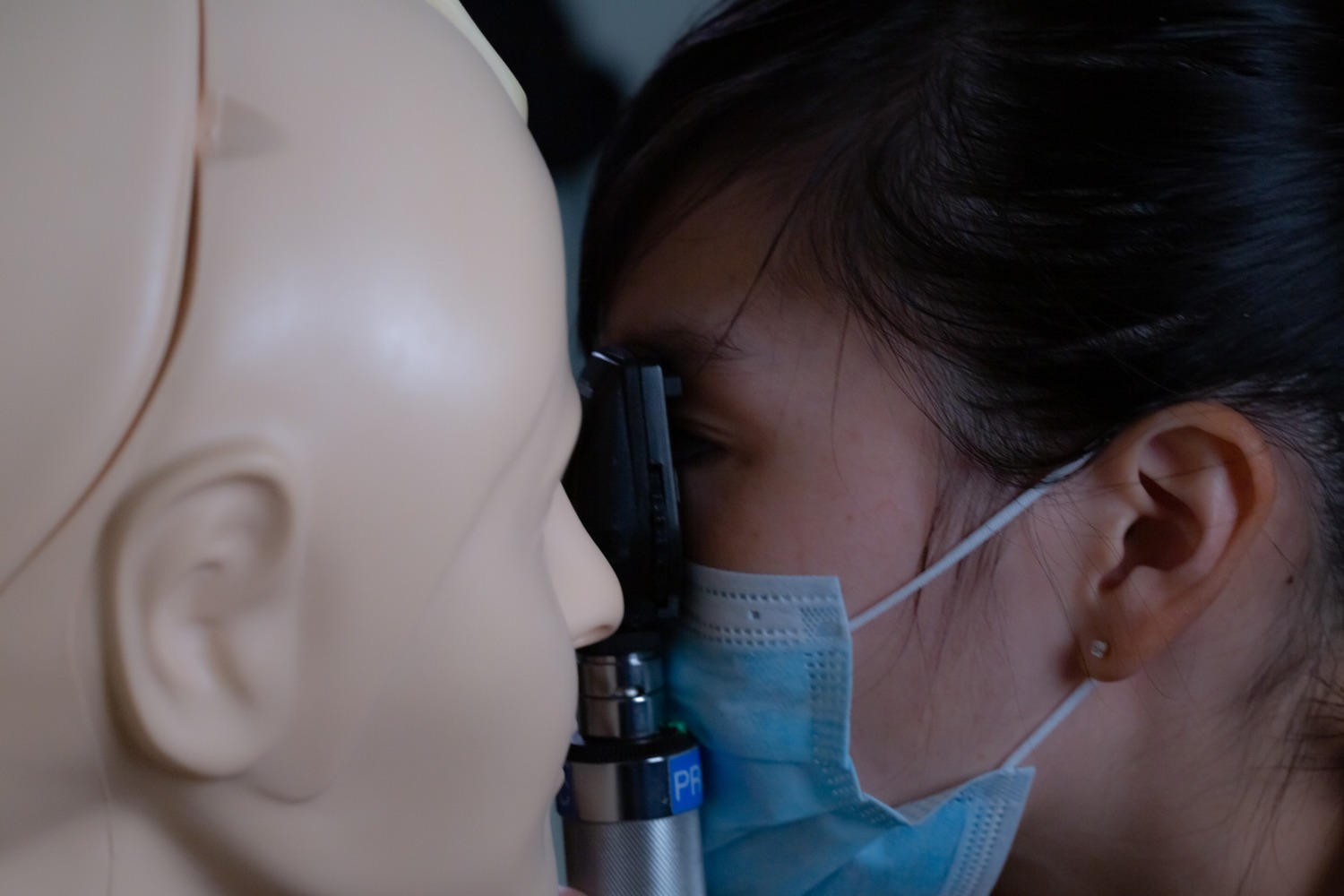

Students learn proper techniques to assist a patient’s breathing // Credit: Duke-NUS Medical School

They also get hands-on with suturing practice and airway management, learning how to reposition a patient’s head to clear airway and assess breathing. For Legaspi-Pelayo, these aren’t just lessons—they are lived experiences. As a former medical technologist, she performed many of these procedures herself.

The unsung heroes of the CPC are, of course, the manikins—inanimate but life-like training tools—and task trainers, which are models that represent an arm, leg, or certain organs, such as a heart.

As realistic models of humans, manikins allow students to get used to handling patients in a safe, controlled manner // Duke-NUS Medical School

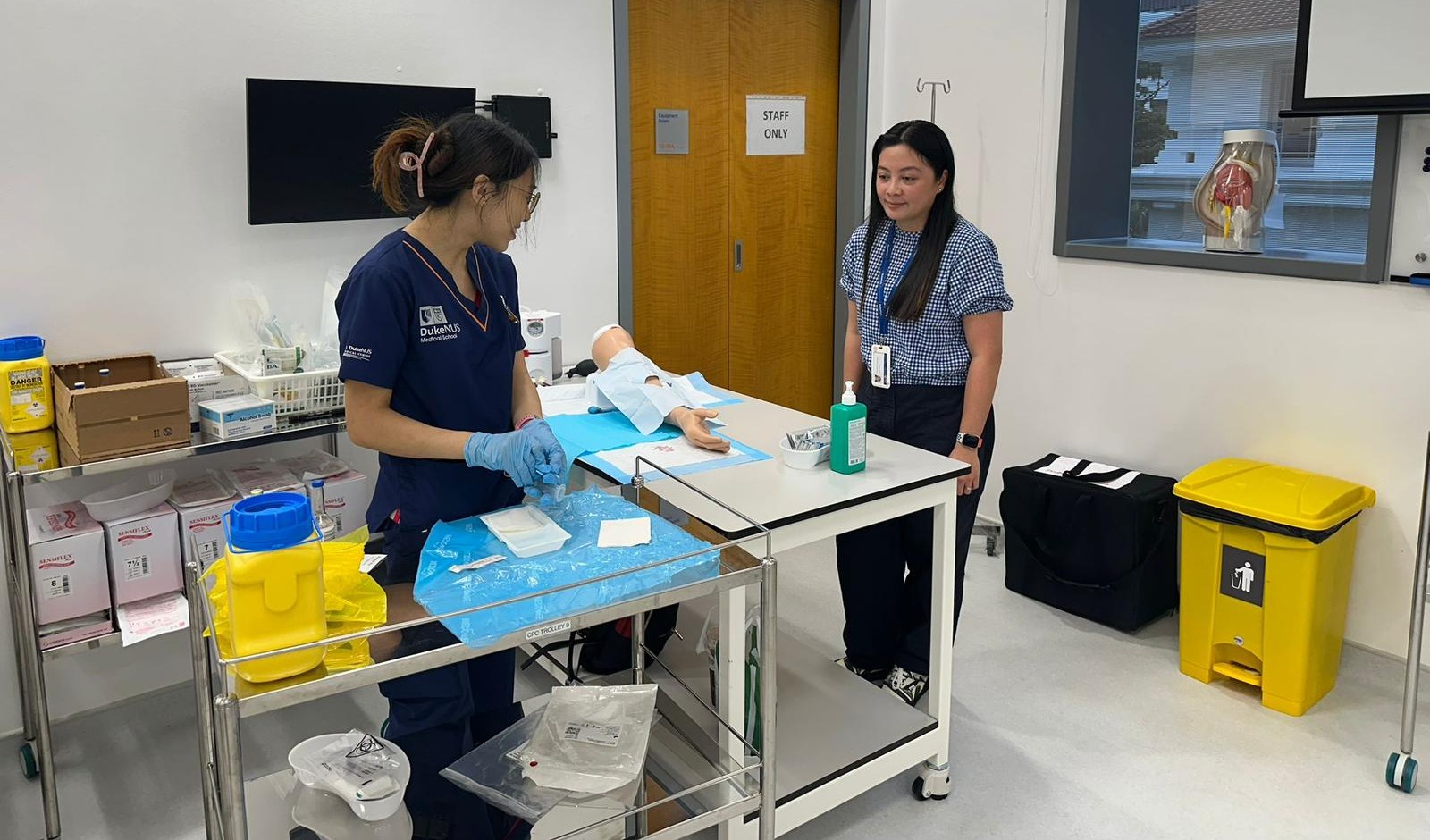

Fountain of knowledge: A student learns to draw blood from a task trainer that models an arm // Credit: Duke-NUS Medical School

Before joining Duke-NUS, however, Legaspi-Pelayo’s teaching leaned more towards traditional lectures. In the Philippines, she taught large cohorts—up to a hundred students at a time, as opposed to small class sizes of four to six—on subjects such as biochemistry, parasitology and microbiology.

“I would say I like both, but when you’re doing a lecture, or even team-based learning, I really enjoy the in-depth discussions we can have. A lot of the time, in procedural skills teaching, it’s more about us demonstrating and then observing the students’ technical abilities, then giving them feedback,” she smiled, a nurturing instinct evident in her gaze.

Legaspi-Pelayo observes a Year 2 student inside the Procedural Skills Learning Lab performing an aseptic blood culture collection procedure. After the procedure is completed, Legaspi-Pelayo plans to provide constructive feedback // Credit: Nikki Legaspi-Pelayo

Legaspi-Pelayo’s day typically begins around 9.30 in the morning, where she prepares the learning laboratory with the necessary requisites, such as medical consumables (think IV tubes and gloves), as well as the willing subjects, the task trainers, for the students’ arrival. Once the students settle in for their independent skills practice, which takes about three hours, she busies herself with administrative tasks, such as working on lesson materials for other modules. Here, students encounter immunology, pharmacology and pathology, amongst other foundations of the discipline. By 1 in the afternoon, she will start preparing the lab for the next group of students. By the time they are finished, Legaspi-Pelayo must clean up the stations for the following day. Occasionally, students will even request her supervision, where she will spend additional hours with them.

However, what motivates her most, without question, is the students.

“Yes, yes, yes. Interacting with students is my favourite part of the job.”

Bedside manners: In the CPC, the students practise in highly realistic environments, sometimes with staff simulating the patients’ demeanours and physical presence. Often, these simulations use task trainers simultaneously to allow students the necessary practice to perform the procedures. Handle with care! // Credit: Duke-NUS Medical School

A watchful eye: Legaspi-Pelayo’s colleague, Calvin Tan, supervises the students’ independent skills practice // Credit: Duke-NUS Medical School

One moment stands out. Last year, a student failed an all-day procedural skills examination after sitting through three consecutive summative assessments. She had to return to the CPC for remedial supervised sessions. Legaspi-Pelayo and her colleague, Calvin Tan, rallied around the student—coming in after hours, on evenings and weekends, to helping her regain confidence and competence.

“She passed,” said Legaspi-Pelayo, smiling. “That one really warmed my heart, when she finally did it. After, she even gave us a bouquet of flowers and a gift basket.”

What gratifies Legaspi-Pelayo is seeing a student grasp the material and gain confidence. To her, it’s all about sharing—one of her strengths, she feels, is helping students understand complex concepts in a simple way. When students master the subject matter, she shares their glowing sense of accomplishment. It’s one of the best parts of her job, and why she enjoys teaching so profoundly.

That’s not to say it’s all smooth sailing. Currently, she and Tan are the only ones manning the CPC’s physical operations—setting up and taking down stations, managing consumables, and prepping materials—making it a physically demanding job that requires a good deal of stamina.

Her advice to nervous students? Just keep practising.

“You just need to practise to really enhance your procedural skills and perform to the best of your ability. In time, when you’re in the hospitals, you’ll have to do those duties, regardless. So expose yourself to as much practice as you can, while you can. Take the chance to do it, because that’s where you learn the best.”

Legaspi-Pelayo notices the newer students—especially in Years One and Two—are often the most enthusiastic to start drawing blood or inserting catheters.

“They are even excited about the hand hygiene procedures,” she laughed. “They really take their time to wash their hands, scrubbing carefully. It’s lovely to see.”

That same sense of curiosity and wonder has always guided her. Even as a student, she was driven to share knowledge—whether by helping classmates review material, preparing notes, or explaining difficult concepts. It’s a pattern that’s followed her into adulthood.

“When I was young, even from when I was in primary school, I was always predisposed towards teaching my classmates what I knew. I would make notes and pass them on to my classmates, and this continued even in my medical school days. I’m always happy to see my classmates pass their examinations, feeling that I’m part of their success as we go through our med school journey together.”

Her path to medicine was sparked by her mother, who once said the family had enough architects and an engineer—it was time for a doctor. Legaspi-Pelayo made that vision her own— balancing both clinical knowledge and educational impact.

“She planted the seed. My mom told me, you should be a doctor. I felt that it would be nice to help people out, either when they get sick, or by teaching them.”

She earned her MD from the Southwestern University School of Medicine in Cebu, Philippines, and later completed a Master’s in Public Health at the University of Malaya. In 2022, she and her husband moved to Singapore, where she joined Duke-NUS while he took on a new role in IT.

The support she receives at work—particularly the healthy work-life balance and autonomy—helps keep her energised, but what truly fuels her is student connection. Seeing the students is the thing that keeps a smile on her face and pep in her step.

The CPC itself is evolving too. Now integrated under the MD programme rather than the Technology-Enhanced Learning and Innovation programme, its role is more closely tied to the core curriculum. Legaspi-Pelayo’s responsibilities are growing in tandem—she now facilitates Year One team-based learning sessions, and even supports the development of learning materials.

Said Legaspi-Pelayo, a rush of enthusiasm for the future apparent in her voice, “I’m grateful that I’m now a part of it, because that’s like what I’ve been doing previously—discussions with the class. Now that I’m facilitating the discussion, I meet both the students and the content experts—and sometimes also in the creation of the resource materials. So, I’m kind of going to where I really aspire to be.”

To be a professor or educator, ultimately, is where Legaspi-Pelayo has set her sights. She says her dream role is to create resources and content as well as teach—the thirst for knowledge that can be passed down is a vital undercurrent in all of her goals.

In many ways, Legaspi-Pelayo’s journey mirrors the rhythm of medical education itself, a continuous cycle of learning, practising, and sharing. From her early days guiding classmates, to today’s hands-on teaching at the CPC, she reminds us that behind every skill gained, is a teacher who made the time to pass it on.

-sharing-a-happy-moment-of-camaraderie-with-her-team-members-in-the-clinical-performance-centre.jpeg?sfvrsn=e0bcf1d6_2)