In the busy trauma wards of the Jaffna Teaching Hospital, open leg fractures stream in. Mostly from motorcycle accidents, with more than a few farmers falling from the region’s tall Palmyra and coconut trees. The injuries sustained while simply trying to make a living, carry a weight beyond physical trauma: their future ability to work and support their families hangs in the balance, determined by the quality of surgery they receive.

These cases drive an innovative collaboration between SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre, SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute (SDGHI) and partners from the University of Jaffna, Teaching Hospital Jaffna, the Harvard Global Orthopaedics Collaborative and SONA global. Together, the partners are conducting a clinical trial of a new, low-cost medical device called the AEFIX clamp as an alternative for treating severe leg fractures. The initiative, part of ongoing efforts in Sri Lanka, began with hands-on training sessions for local healthcare staff on how to use the device.

Beyond the hospital walls

I quickly learned a more powerful lesson. To truly help, one has to have a real understanding of the local context. To fix unfairness in healthcare, it is essential we look beyond the hospital walls and see how people really live and work.

One patient’s case was especially memorable for me. He had been in a road traffic accident and was part of the study comparing external fixation methods of open fractures. Because he was in the control group, he had been treated with one of the standard devices regularly used in Jaffna instead of the new affordable AEFIX clamp. When I spoke with Dr Siva, the first-year medical registrar on duty who explained the details of the case, it struck me that this was more than just a clinical issue. It was about accessibility—that patients could find treatment without the added burden of financial hardship.

In Sri Lanka, the high cost of essential trauma care, such as open fracture treatment, limits access for many people. Patients often face considerable out-of-pocket expenses, forcing families to balance medical needs against financial hardship. While external fixation, particularly the clamps, is vital for treating open fractures, these components are expensive and often unaffordable in low- and middle-income countries. The AEFIX study aims to determine if a significantly cheaper clamp can offer outcomes that are equally good or better than with the available standard care options in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province. Without timely and effective treatment, open fracture patients risk death, amputation or permanent disability.

Breaking barriers as a student

One of the most daunting yet empowering moments came during the AEFIX workshop. I found myself guiding doctors, interns and trainees through the assembly of the device.

As a student, I was nervous. Who was I to demonstrate and guide trained doctors and nurses? The technical vocabulary and the language barrier only made it even trickier for some. They listened attentively and with the aid of some non-verbal communication, were able to try it out successfully and even requested feedback. I was heartened to realise then that I could contribute meaningfully even as the most junior member of the team.

Furthermore, I had never learnt anything about orthopaedics in medical school yet. This trip was my first deep dive into fracture care and surgical devices. To be trusted with a hands-on role in such a specialised area was humbling. It showed me how much you can learn when you step outside the classroom and immerse yourself in real world global health practice.

Innovation through collaboration

What stood out to me most was the collaborative spirit in the room. The Sri Lankan surgeons didn’t just adopt the device as it was presented. Rather, we all put their heads together to see how it could be improved. They suggested changes to make the packaging lighter, the kit smaller and the assembly easier.

Those conversations showed me that innovation isn’t something you simply deliver to a community, but something you build together. I learnt the importance of partnership. Our role wasn’t to impose solutions, but to co-create them—respecting local expertise, listening to practical insights, and working as equals. In those moments, I truly saw the strength and value of collaboration across borders.

Lessons in resilience

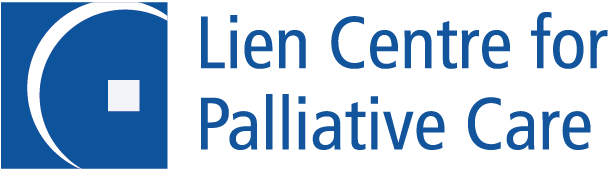

Inside the operating theatre, I witnessed resilience in its purest form. In the modest Casualty OT, surgeons performed as many as three operations at one time, sharing a single orthopaedic drill between them. One of the operating tables even had a broken height adjustment mechanism, leaving anaesthetists and surgeons to work in awkward positions. Yet through it all, the team pressed on, calm, efficient, and entirely without complaint.

When I visited the anatomy lab at the University of Jaffna’s Faculty of Medicine, I found the space warm and basic, with cadaver preservation measures kept simple. We were given just latex gloves and face masks, in stark contrast to the full disposable PPE that I’d always taken for granted in Singapore. Watching the doctors crowd around the cadavers, eagerly discussing structures despite the limitations, was humbling. I realised how privileged I have been in my own training, and how much responsibility comes with that privilege.

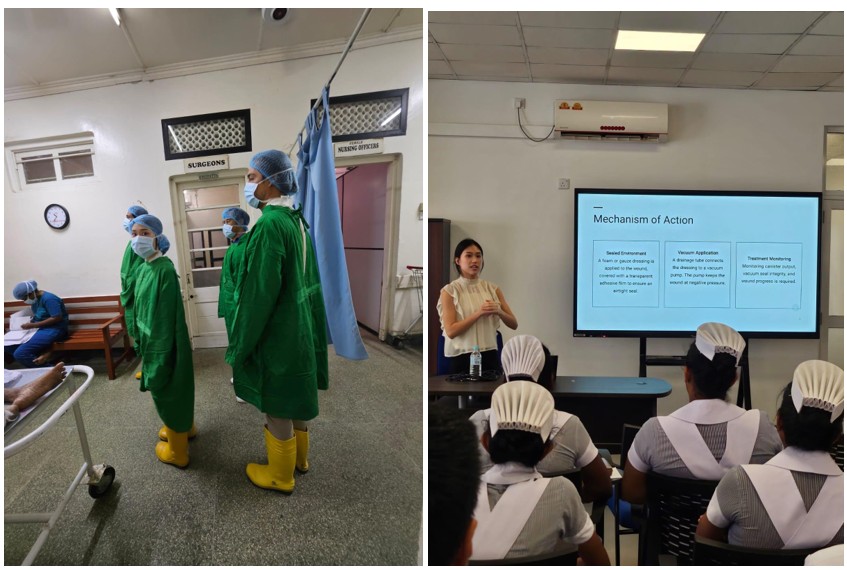

Singapore team gowning up to enter emergency operating theatre and Goh Xuan Ying presenting on wound care at the workshop // Credit: Courtesy of SDGHI

Lessons in humanity?

Amid the gravity of our work, there were moments of lightness that reminded me of our shared humanity. At a wound care workshop, I spoke about negative pressure wound therapy, a technique that is commonplace in Singapore but less accessible in Jaffna due to its cost. The Sri Lankan nurses were eager learners, quick to grasp new concepts, and generous in sharing the ways they had improvised with limited resources.

At one point, a nurse quipped that the negative pressure machine looked like a fancy vacuum cleaner and wondered aloud if it might double as a tool for household chores. Laughter rippled through the group, and for that moment, the atmosphere lifted.

It was a simple but powerful reminder that no matter where we practise, we are united by the same purpose: to care for our patients as best as we can.

What I carried home

This trip taught me that more than just clinical skill, medicine is also about context. Effective treatment must align with financial realities, cultural understanding, and respect for local practices. Healthcare innovation is not defined by the newest or most advanced technology, but by relevance, by meeting patients and providers where they are.

I returned to Singapore with a clearer vision of the doctor I hope to become: one who listens closely, collaborates deeply and places empathy at the heart of care.

Most of all, I learnt that even as a student, I have a role to play. With open ears and willing hands, I can help shape a future where care is not only advanced, but also fair, accessible, and deeply human.