Before the grants and ground-breaking research, before deanships and academic accolades, there was always music. A guitar in his hands. A rhythm in his head, fingers tapping. A need to make sense of things by playing his way through them.

“Playing clears my mind,” said Tom Coffman who first picked up a guitar when he was 11. “But I have to be careful not to play too late at night—it gets me so wired I can’t sleep.”

It’s the same restless energy that’s propelled him through a career marked not by easy turns, but by reinvention: from a free-spirited surfer in Puerto Rico to business student stumbling through economics, to a clinician-scientist who found clarity in discovery and purpose in people. Eventually, the nephrologist became the longest-serving dean of Singapore’s only graduate-entry medical school. The strings were always there—he just kept finding new ways to tune them.

Music never left. It accompanied him through lonely nights and scientific breakthroughs, helped him shake off work, connect with his sons, and on more than one occasion, fill a room with joy.

“One of the great things to do is play music live for a crowd—that’s just a blast,” said Tom. “If I wasn’t doing this, I’d probably still be doing that.”

Making his own six-string to play the tune of his life

For a young Tom, music provided an anchor when home didn’t. His family moved frequently: Western Virginia. Tennessee. Ohio.

“I loved my parents, but the relationship was somewhat tortured and complex. As soon as I was old enough, I got out of the house as much as I could,” he recalled.

After the family finally settled in Puerto Rico, this meant spending time at the beach. “I spent every waking moment being in the ocean, surfing or snorkeling.”

His fascination with the ocean almost led to a degree in marine biology. Instead, lured towards more solid ground by an offer from Wharton Business School, he first tried following in his father’s footsteps. But during an early economics course, Tom found that he “just couldn’t make sense of it”.

What did make sense were science and math. Working in a virology lab resonated even more. But what truly made his heart sing was puzzling out a patient’s symptoms to arrive at a diagnosis.

After excelling in pre-medicine, he enrolled in a Duke-NUS-like medical programme at Ohio State. Seizing the chance to spend a year in the lab, he headed back to Philadelphia to join a lab focusing on kidney research.

“I made some esoteric discoveries,” said Tom, that resulted, among others, in a first-author paper on the parathyroid hormone in kidney physiology. But what got him hooked was the feeling.

“It was awesome to create new knowledge,” he said.

Philadelphia also held another string to his heart: his then-girlfriend, now wife, whom he met at the University of Pennsylvania while she worked in the medical ICU.

After he graduated from medical school, the couple moved to Durham for Tom’s residency at Duke.

“I have always been a learn-by-doing kind of person and Duke’s residency was known as a residency where you got to dive in and do a lot of patient care,” he said.

Even as a young resident, Tom’s brilliance shone, as Duke School of Medicine Dean Professor Mary Klotman recalled:

“Tom and I were residents in internal medicine together at Duke, a somewhat intimidating residency known for its academic excellence. He rapidly developed a reputation for not only being incredibly smart and intellectually curious, but also for being a real team player.”

Added Klotman: “His understated demeanor made him very approachable. These characteristics have defined Tom throughout his career.”

Following his residency, he specialised in nephrology, pursuing both clinical and research work.

But as a young faculty member, Tom’s department chair urged him to add “more tools” to his toolbox—advice that would prove transformative.

Tom applied to do a sabbatical with Oliver Smithies, a geneticist whose work would, some 17 years later, earn Smithies a Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.

Rather than any specific personal quality, Tom reckons it was his offer to work for free and assist Smithies’ postdocs in any way, that got him through the door.

Reflecting on the experience, he called it a “huge confidence boost” for a young researcher. “It was an amazing atmosphere. Oliver’s approach to science, life and thinking about discovery was incredible,” he said. “It taught me the value of interdisciplinary interactions in medical research.”

Enjoying the new-found harmonies

Over the next two decades, the two mapped the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, the hormone system regulating blood pressure and fluid balance.

“Tom and I were residents in internal medicine together at Duke, a somewhat intimidating residency known for its academic excellence. He rapidly developed a reputation for not only being incredibly smart and intellectually curious, but also for being a real team player.”

“We applied Oliver’s technology to knock out all the genes in this pathway in mice to understand their impact on blood pressure and kidney function,” said Tom.

They clarified how widely used blood pressure drugs worked. Then they expanded their mouse model to kidney disease, which is inextricable from diabetes and high blood pressure—a puzzle that continues to fuel Tom’s research to this day.

During the same period, Tom rose through the ranks at Duke to become division chief for nephrology, a role he loved. He could continue with his clinical and research work, while helping others build their careers. It was, in his words, “the perfect balance”.

“I got to help people execute their careers, as clinicians, scientists or a mix of the two,” said Tom, who remains committed to mentoring others.

He also knew that success required more than mentorship. He needed a conducive environment. To augment what was already in place, he set up the National Institutes of Health-funded O’Brien Centre for Kidney Disease at Duke. Through it, he aimed to “attract new scientists with new perspectives” who would advance research at the intersection of cardiovascular and kidney disease.

And it wasn’t just at Duke where his career flourished. In 2008, he was elected president of the American Society of Nephrology. His predecessor in the post, Peter Aronson, said at the time: “I am truly pleased to pass the gavel to Tom Coffman, who is one of the most distinguished academic nephrologists in the world.”

An interlude to tune the strings

Since his high school days in Puerto Rico, Tom turned to music to provide a healthy perspective on the wider world.

“When I was in college, I played in this acoustic band at fraternity parties and things like that. And then as a resident and fellow in medical training, I started playing with a band of fellow physicians and hospital staff,” he said.

A modern soul group, the band performed around Durham and practiced in Tom’s basement.

“Tom started his band, Blast Crisis, while a resident at Duke. We had the pleasure of hearing the band a number of times at local clubs and they were really good…including Tom!” recalled Klotman.

“I used to be jealous that he had the perfect escape valve for an intense residency. Not surprising, Tom was able to build a very talented group…using the same people skills that he has used to build his teams in medicine,” she added.

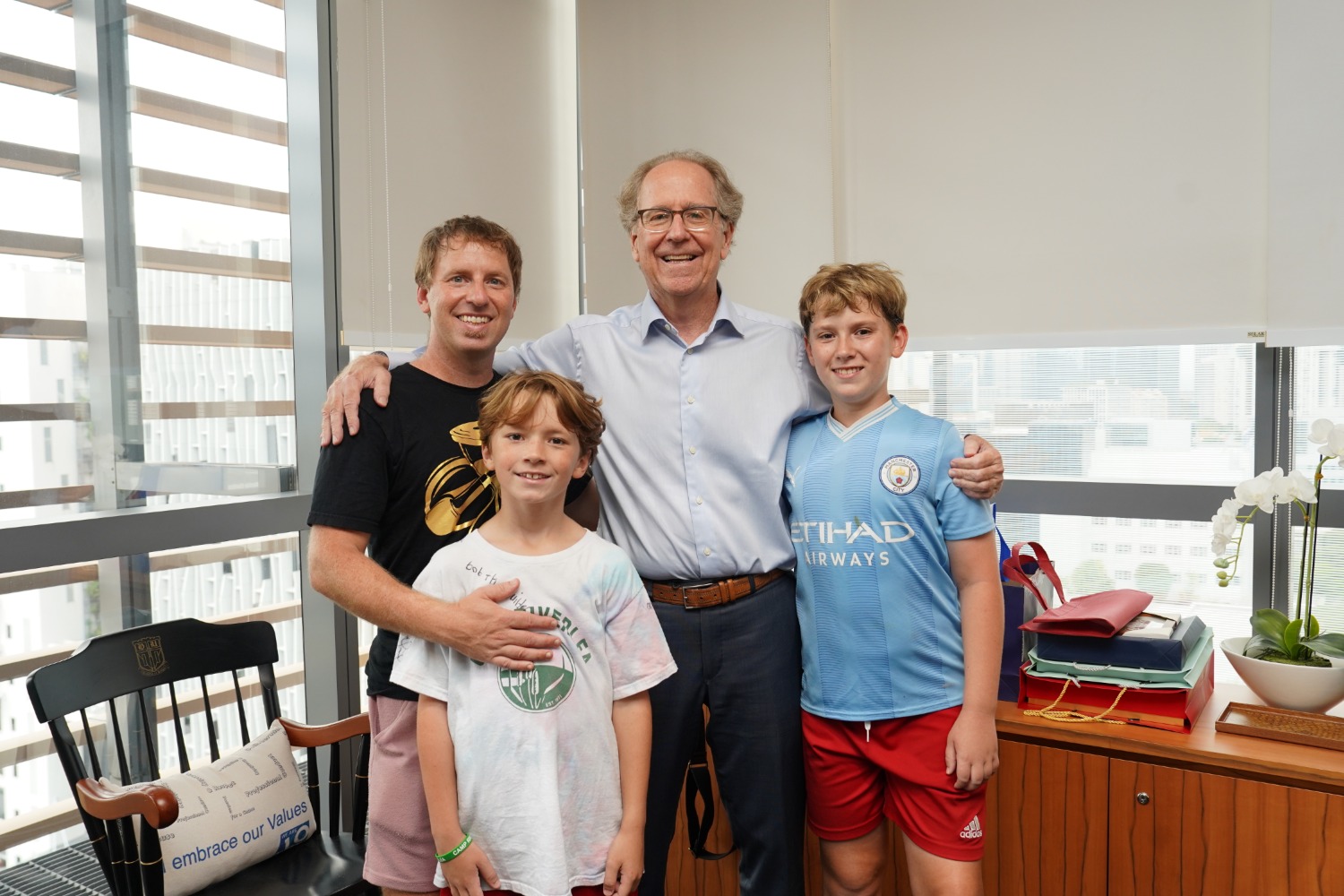

To repay his family, which had grown to include three sons, for their support, Tom made sure to be present for games, concerts (one of his sons is now a professional musician), and important events in the boys’ lives. He even took them, in turn, to conferences.

But he was also an influence at home. There, he was in charge of the kitchen.

“For me, cooking is an expression of love and friendship,” said Tom, who passed his flair for flavours on to his sons.

Saturday morning pancakes were a fixture during his sons’ youth. Now, his grandkids look forward to them. And his flipping skills always made him a crowd favourite at the annual Deans’ Pancake Breakfast.

Courage to master a new tune

Content though he was, after more than two decades at Duke, Tom was ready for something new. Hearing this, then-Chancellor for Health Affairs at Duke, Victor Dzau, offered him a proposal: The chance to build twin programmes in Durham and Singapore. Tom was intrigued.

Pat Casey, the hiring manager on the Duke-NUS side, said Tom ticked all the boxes: a clinician and first-rate scientist who was passionate about developing others. He also had to be, in Casey’s view “highly credible and a good judge of talent and science”. Another box Tom ticked.

With the imagination to see the potential, Tom accepted. In 2010, he became the founding director of the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders (CVMD) Programme, while helming a new Cardiovascular Research Centre at Duke.

Tom’s time in Singapore and the programme grew apace, as he assembled a “pretty good group”.

“I thought the challenge would be recruiting world-class scientists, but that turned out to be surprisingly easy,” he said.

The programme grew from 2.5 to 10 faculty, a who’s who of international scientists and promising young researchers. Within five years, the team secured more than S$40 million in competitive research grants.

One of the final recruits under Tom’s tenure was systems geneticist Enrico Petretto, who said: “Tom invested a lot in people and recruited some of the best scientists. He is a leader of people—that’s not something you can learn at school.”

“He could get all the best scientists and clinicians into the same boat, which is not easy, especially as they are from very different backgrounds.”

Then broke the news that Dean Ranga Krishnan was stepping down. In the search for a successor with strong ties to Duke, Tom’s name soon rose to the fore.

“When I was asked if I was interested,” Tom said, “I said, yeah, maybe.”

This hadn’t been part of the plan, but Tom felt his strengths in operationalising big plans and uniting people behind a shared vision, would make him the right candidate for the job:

“I felt that this was a good role for me. As someone who came up through an academic medical centre (AMC), I could help get the School and AMC to the next level, becoming a mature, established part of the ecosystem and excelling in that space.”

And unlike in the US, this role did not include overseeing clinical operations, giving Tom the opportunity, when the time was right, to expand his research to Singapore—an opportunity he seized in 2017.

He marshalled scientists and clinicians from 24 institutions to form the “Diabetes study in nephropathy and other microvascular complications” or DYNAMO. DYNAMO was Duke-NUS’ first S$25 million Open-Fund Large-Collaborative Grant awarded by the National Medical Research Council. It was recently renewed for another S$25 million.

And to Petretto, it is a perfect example of Tom’s special knack—that ability to bring people together:

“He could get all the best scientists and clinicians into the same boat, which is not easy, especially as they are from very different backgrounds.”

Joining a new band, finding his own rhythm

But as the new dean, his first order of business was to create an environment at Duke-NUS that provided “people the space and framework to function optimally, be creative and help develop a shared vision”, he said.

One thing was: The School was as good as its graduates. So when he found out, during his early months as dean, that the reputation of Duke-NUS graduates was less than stellar, he had to act.

Tom recalled: “It was alarming, but I also didn’t believe all the feedback—some of the perceptions were not correct, so we had to fix it.”

“He is open to trying new things, to innovate within the curriculum, which enabled us to be nimbler.”

And he had to fix it for the students, too. Because they were starting to doubt their own readiness, with only just over a quarter reporting they felt confident at the end of the programme.

With the education team, he tightened assessments, expanded clinical clerkships and added a Year 4 capstone project to ensure students were ready for work.

“He is open to trying new things, to innovate within the curriculum, which enabled us to be nimbler,” said Shiva Sarraf-Yazdi, who now leads the education office.

This included novel ways of creating longitudinal experiences, where students revisit similar experiences to build their skills. The pilot was a success, but the initial format was not scalable.

“I give a lot of credit to Shiva and the team for this. They figured out a way to integrate it with the rest of the more standard curriculum,” said Tom.

Today, almost nine in ten Year 4 students report that they feel confident about starting clinical work.

But Duke-NUS has a special mission: To train clinician-scientists, something no medical school can accomplish alone.

“Having been embedded in a high-quality centre, I knew what was needed and could relate to the pain-points. So, I spent a lot of time to cultivate relationships,” said Tom.

“Tom’s biggest legacy is that he took a school and made it a critical partner in a globally leading AMC. The partnership is now on solid ground and he’s leaving it poised to be among the top three in the world.”

Together with Ivy Ng, who was then the head of SingHealth, he charted new waters, creating the initial blueprints for a thriving AMC.

“Tom is tremendously patient. He also has a quiet resolve to see things through. I found that very helpful in the entire journey,” said Ng.

Regular un-minuted meetings between the two, to smoothen out even the most difficult issues, further strengthened the partnership.

For Tom, having Ng as a partner fully vested in academic medicine was key to their joint success: “Ivy has been an unbelievable partner in this. She was essential for this.”

To maximise the School’s impact, Tom directed significant investment into the Centre for Clinician-Scientist Development, which supports clinician-scientists across career stages, and approved a new PhD programme aimed at working clinicians, which was introduced in 2018.

Today, the AMC is home to 74 nationally funded clinician-scientists, up from 20 in 2010. Between them, they’ve received 20 Singapore Translational Research Investigator and 75 Clinician-Scientist Awards.

“Tom’s biggest legacy,” said Ng, “is that he took a school and made it a critical partner in a globally leading AMC. The partnership is now on solid ground and he’s leaving it poised to be among the top three in the world.”

.jpg?sfvrsn=d7d3c0e7_0)